Rebuilding Gather’s virtual world brick by brick

Why it took us five years to let your avatar sit down

Background

Gather scaled extremely quickly in its early days during the pandemic across a multitude of use cases like virtual classrooms, online conferences and remote offices. An unfortunate side effect was we didn’t have a lot of time to design a scalable and maintainable foundation for the virtual world. A siloed tool called Mapmaker allowed users to make map changes on the client before saving it as a schema-less document in Firestore. This suited our needs in the beginning: we didn’t expect a space’s map to change frequently and typically there would be only one editor at a time. As the product changed and grew, we started to experience its limitations.

{

"dimensions": [100, 100],

"collisions": { "2": {"8": true, "9": true} ... },

"backgroundImagePath": "https://cdn.gather.town/...",

"areas": {

"1": {

"coords": [{"x": 8, "y": 11}, {"x": 9, "y": 11}, ...],

"name": "Blue Meeting Room",

}

},

"foregroundImagePath": "https://cdn.gather.town/...",

"objects": {

"jukebox": {

"x": 15,

"y": 3,

"url": "https://cdn.gather.town/...",

"width": 1,

"height": 2,

"previewMessage": "Press x to control jukebox",

}

...

}

}Cracks in the facade

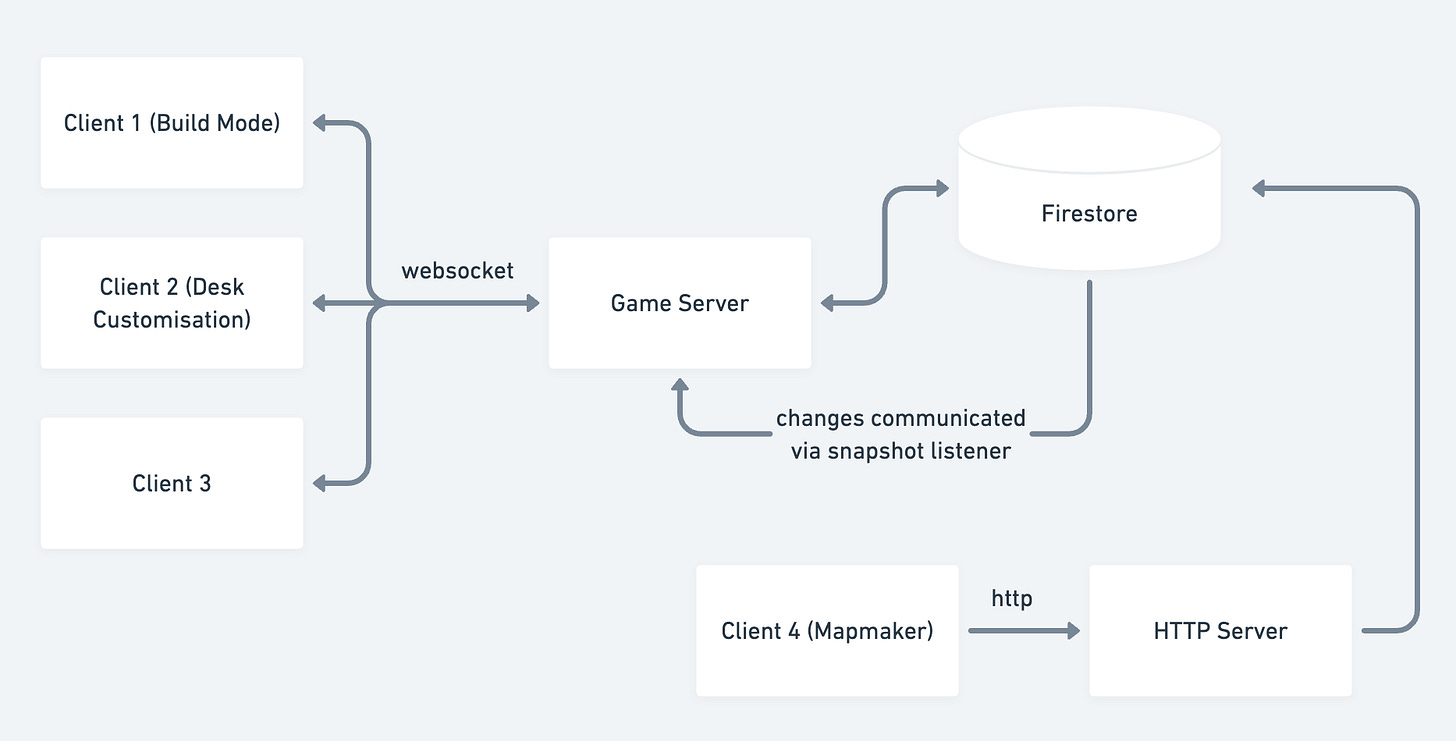

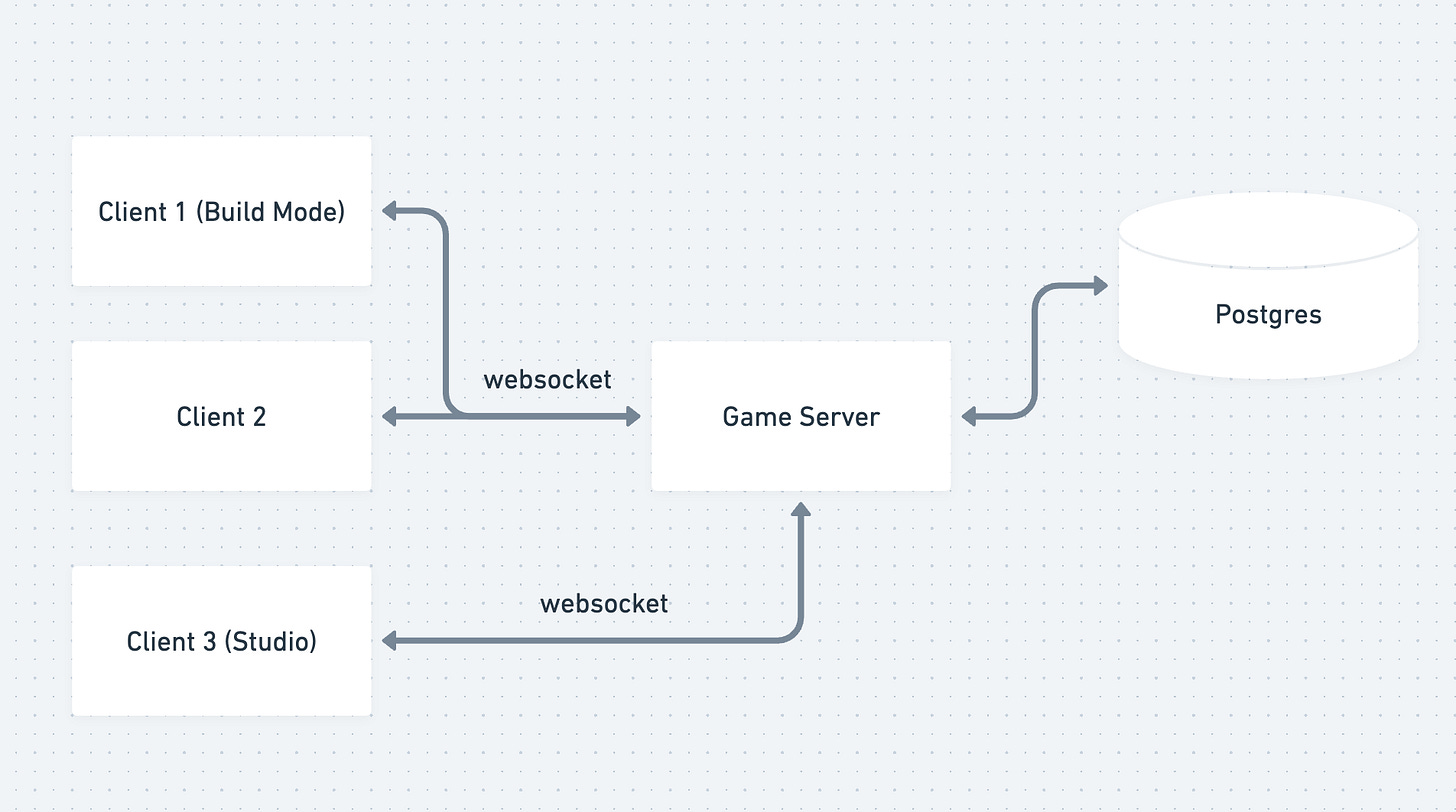

When Gather expanded to supporting remote offices, we built real-time features that allowed users to decorate their desks in app. All real-time collaborative features had to communicate with our stateful game servers via websockets so changes can be propagated to all online clients connected to the same space. We very quickly ended up with 3 divergent map-building tools on 2 different architectures that didn’t talk to each other.

Glaring problems started to appear:

A user painstakingly decorated their desk. An office admin making changes to the office simultaneously in Mapmaker could accidentally overwrite the user’s changes.

Code couldn’t be abstracted and shared easily as the tools were built with different paradigms. Mapmaker would send the entire map over the network to be persisted while real-time map tools were sending delta packets via a websocket. Each time a new feature, e.g. multi-select, was introduced, it had to be re-written for each tool.

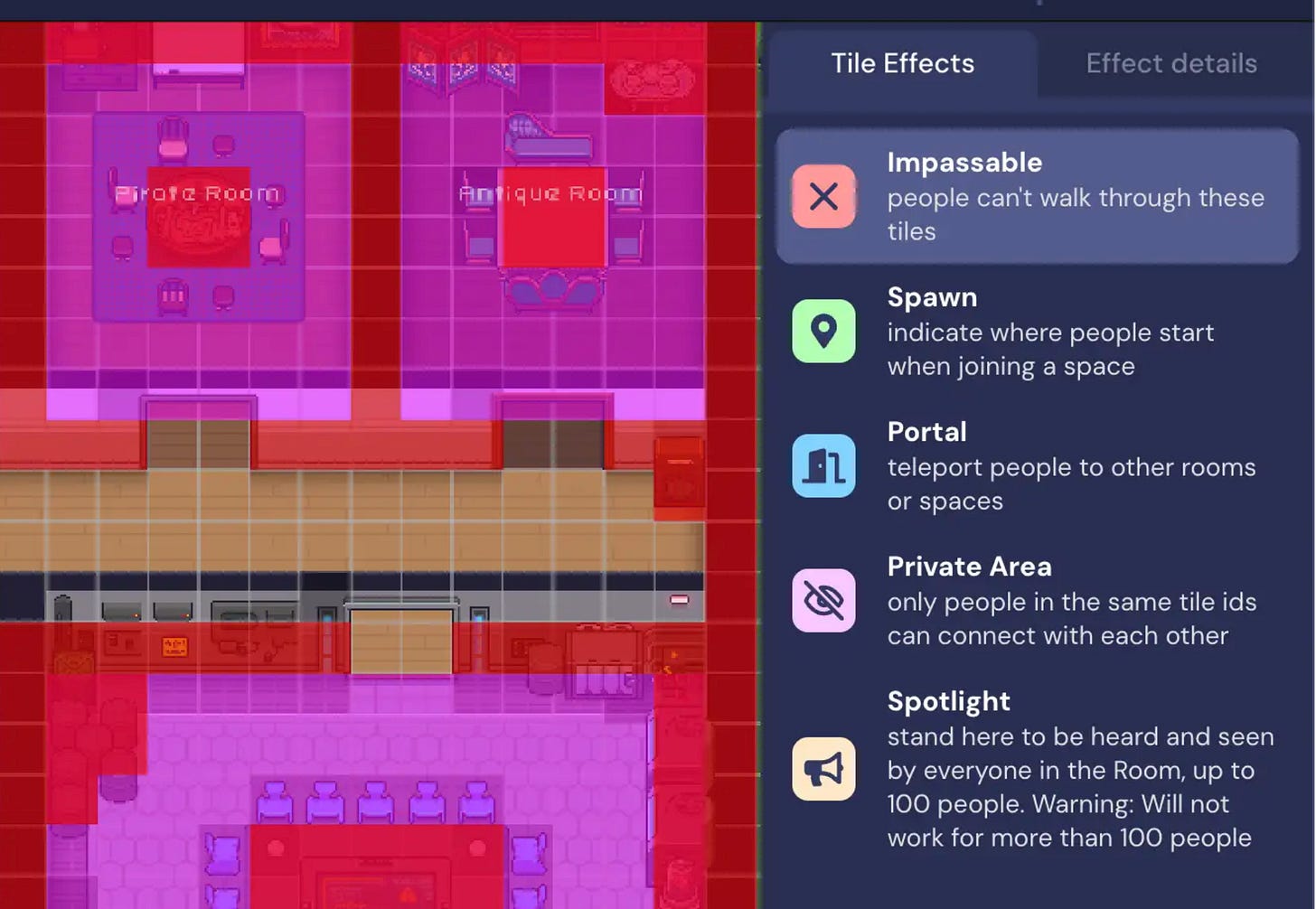

Objects didn’t have real behaviour. Each object is an image stamped on top of a background and what makes an office have any utility is a grid of “tile effects”. For example, if you wanted to prevent people from walking through a table, you had to use tile effects to mark the coordinates beneath the table as impassable.

Unlike event spaces that mainly required upfront effort to create a great map, office maps required constant maintenance. A company is a living, growing entity: people join and leave, teams expand and shrink. Mapmaker was becoming a real bottleneck for supporting large customers who tend to make changes frequently or expanding usage from an internal champion’s team to other teams. As our remote work product scaled, users frequently complained about how hard it is to update their virtual office:

Reconfigurations would take hours. The flooring and walls were a large, static background image with furniture and decorations layered on top via Mapmaker. Objects didn’t understand how they’re related to each other or to the map as a whole. This meant moving a table didn’t move all the objects on top of it or the tile effects underneath it. Objects were also layered in the order that they were placed — you couldn’t place an object behind another object without re-stamping the latter.

Users found the existing UX patterns unintuitive. Our tools didn’t talk to each other and gradually had divergent behaviour, e.g. undo exists in Mapmaker but not Build Mode. Mapmaker was originally inspired by game level design patterns where you incrementally layer more complexity onto a map. What users expected was interaction patterns like dragging and dropping objects or even entire rooms into their office.

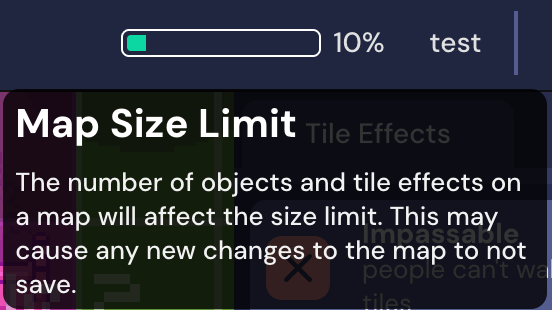

Firestore became a real constraint for us over time. With how much users were decorating, maps were starting to come up to Firestore’s 1MB document size limit and we had to impose a seemingly arbitrary object limit in Mapmaker. Our art team couldn’t deprecate old or fix broken objects easily since querying and bulk updating nested data structures in Firestore was non-trivial.

The Rebuild

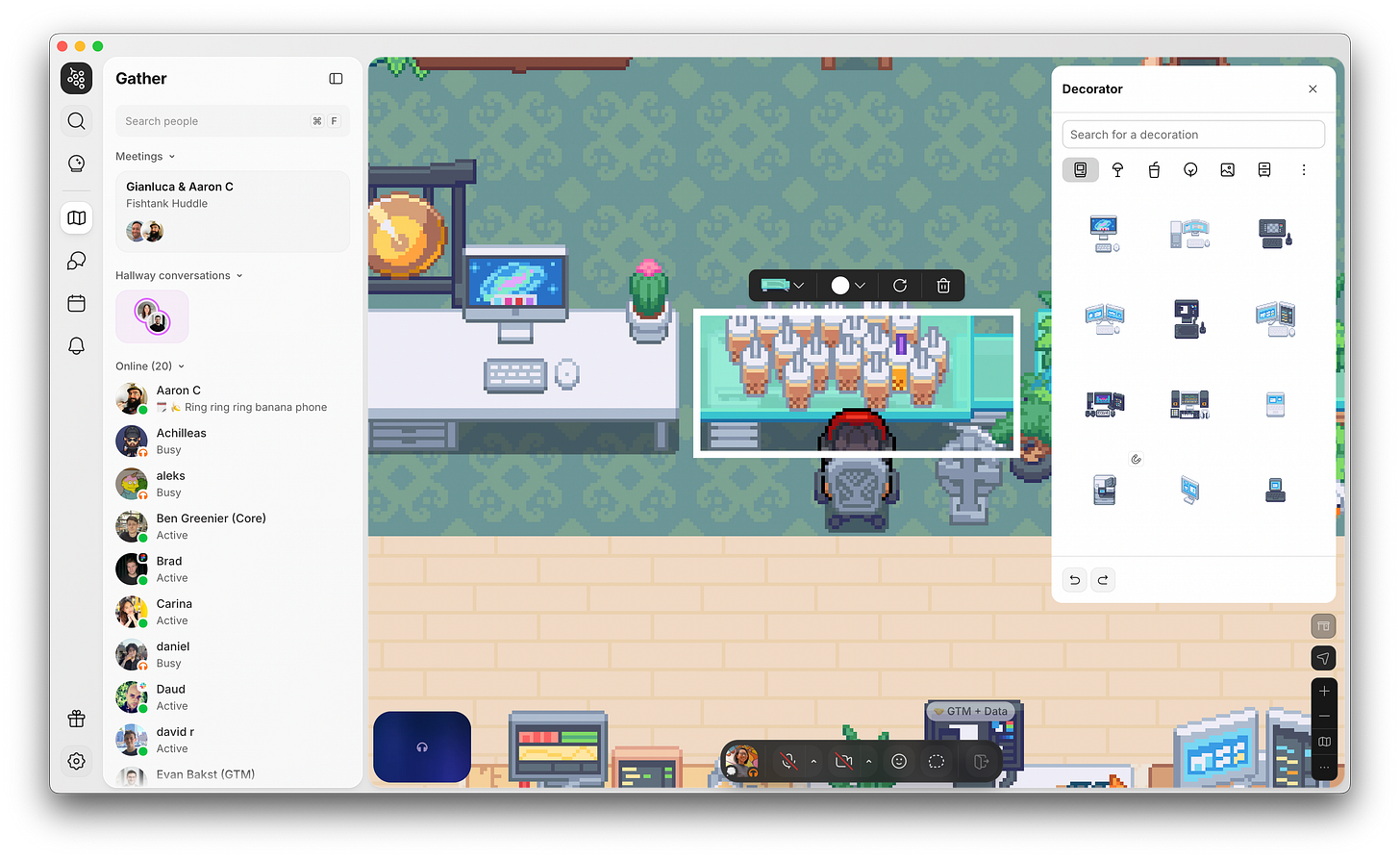

In mid-2024, we gained conviction internally to rewrite Gather with remote work as a first class citizen. This rewrite also gave us the opportunity to completely redesign our map models from the ground up, an effort we had already attempted once and iced a year prior. This was an extremely chaotic (and fun!) time where we were building on top of a new platform with evolving interfaces. Our saving grace was at this point Gather had supported remote offices for two years and we were deeply familiar with the use cases we needed to achieve parity or unblock. This helped us to see around corners and make an opinionated ~6 month roadmap to ship Studio (a la Mapmaker 2.0), Decorator (our in-app map-building tool) and other complementary tools.

Slow is smooth and smooth is fast

As a fast moving startup, we rarely had the luxury of significant upfront planning. After seeing how repeatedly tacking behaviours on top of a poorly expressed system had lowered the ceiling of map building, we decided to invest more than 2 weeks (an eternity for us!) designing, prototyping and brainstorming. To bound the solution space, we created a few guiding principles:

Map models should be governed by generalisable rules that help us to achieve these outcomes:

It should be trivial and performant for users to reconfigure their office.

Objects should have real behaviour. Tile effects should never be something a user needs to understand.

Tools should have a consistent and easy to understand interaction model.

The game server should be the source of truth so changes can be broadcasted to all clients.

Map edits should not be client-only as it was in Mapmaker as we wanted to eventually pave the way to multiplayer edits and conflict resolution.

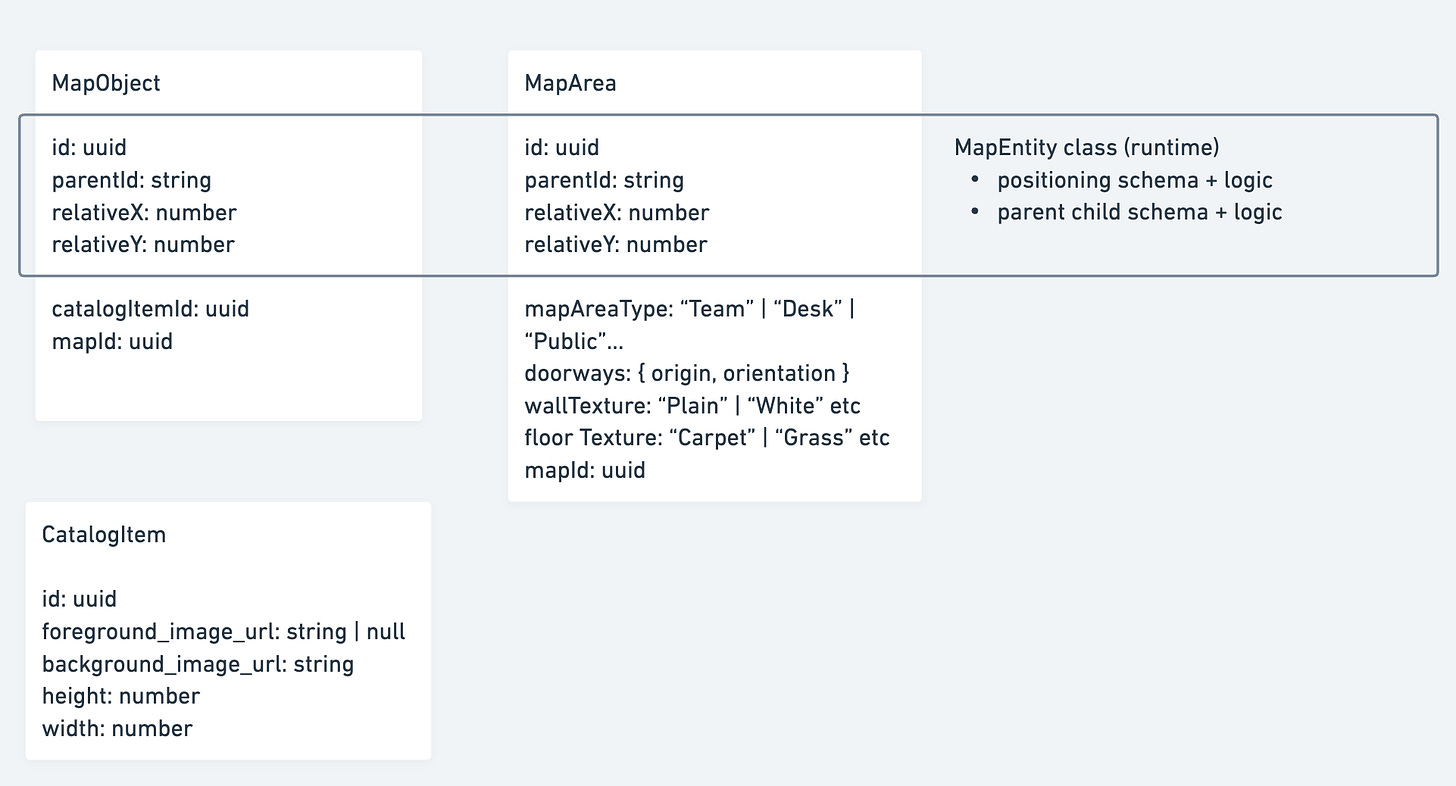

We eventually were able to design an expressive system with a short list of constraints. Everything you see on a map is a map entity: MapObject, MapArea, MapGroup.

Map entities can have parents and children

Map entities have relative properties to their parent

MapObject(user controlled objects) inherits object metadata fromCatalogItem(the master object designed by our art team)

Entities are stored flat in Postgres and reconstructed as a traversable tree on the server and client. Picking a relational data store was very intentional:

Foreign keys guarantees data integrity and prevents orphaned records. We no longer wrote application code that guessed at the schema of maps from Firestore.

It became trivial to deprecate old or fix broken objects with a SQL query.

Users are free of our old Firestore 1MB limit! This unlocked scalability and allowed users to build much richer and more complex maps.

Floor ├── Map 1 (state: draft) │ └── Map Area │ ├── Map Area │ │ └── Map Object │ ├── Map Area │ └── Map Area │ ├── Map Object │ └── Map Object │ ├── Map 2 (state: active) │ └── Map Area │ ├── Map Area │ │ ├── Map Object │ │ └── Map Object │ ├── Map Area │ └── Map Area │ └── Map Group │ ├── Map Object │ └── Map Object │ └── Map (state: archived) └── Map Area ├── Map Area │ ├── Map Object │ └── Map Object └── Map Area ├── Map Object └── Map Object

Once the models were defined, we spent time figuring out their APIs. An exercise we did was working backwards from the end goal — what kind of APIs do we want to work with? We decided early on to lean into OOP patterns as it more naturally composed and encapsulated the behaviour of map entities.

Using a concrete example, we preferred

table.move()andlobby.move()tomove(table)andmove(lobby). Entities inherit default behaviours, e.g. an entity’s position is updated when moved, which could be overridden for more complex use cases, e.g. moving an area will additionally move all users within that area so users don’t end up stranded in a weird spot. A sharedmovefunction would overly generalise and accumulate conditionals for every entity type.

meetingRoom.lock()instead of iterating through all doors in a room and callingdoor.lock(). Areas understand its own state and can propagate state changes to its children. This keeps business logic colocated with the entity that owns it.

We landed with an intuitive common interface (move, delete, duplicate, etc) across all map entities while allowing each entity type to define what these operations actually meant.

Why you’re finally able to sit in a chair

These insights dramatically improved how map entities interact with each other in increasingly complex use cases:

Easily query all children of an entity, e.g. clear all decorations on a desk when a user switches desks.

Deleting a parent cascade deletes its children, e.g. deleting a room also deletes all furniture within the room.

Moving a room only requires updating the relative coordinates of its

MapAreawithout changing all children’s coordinates (which saves a ton of writes to the database).Tile effects are no longer a property exposed to the user. Our art team still uses it to label how an object is impassable, e.g. a tall plant has a single impassable base tile.

Map areas understand where its siblings are and flash red when a user accidentally overlaps them in Studio.

All clients in the same office are connected to the same server and prevented users from clobbering each other’s changes. Last-write-wins ended up being a reasonable approach for conflict resolution since users were not interacting with text on maps (which made OT or CRDT unnecessary). We just had to make sure to update users’ undo-redo stacks when collaborative edits ship in Studio!

Map objects are hydrated with rich metadata from a single copy of catalog items. This reduced the amount of data we were sending over the network as we were not duplicating the same object metadata across n objects. It’s not uncommon for users to have an office with 200 of the same trees!

We can attach bespoke metadata on

MapArea, e.g. alockedboolean. This means all doors within a room can derive their state from their parentMapAreaand stay open or shut. Previously you would have to unlock each door individually.

Reconfiguring an office went from hours to minutes. Engineers also found the APIs easier to work with and were rapidly building more complex features that were not possible before, e.g. desk manager that allows admins to update the seating chart within the office. With relationships and metadata, it became trivial to understand where a chair is in a room by querying all children of a room of type Chair. Users are now navigated to the nearest empty chair after entering a meeting room in Gather 2.0.

Other fun things we learnt

We initially thought we had to build an object layering tool in Studio for users to manually layer objects. We cut it from scope entirely by following a pretty clever 2D game design tip: let the y-coordinate of an entity dictate its depth.

To handle more complex objects like armchairs where you want to selectively render the chair arms in front of the avatar,

CatalogItemsupports a foreground and background image that’s composed together on the client.It’s tricky duplicating maps with a deeply nested, self relational, tree-like structure without hitting FK errors. We were eventually able to duplicate a map with >2000 objects within 250ms by using a nested write in a single database transaction. Even when we start working with very large maps, we can slice the tree horizontally so parents are always written first to the database.

Paving the way forward

Going from hours to minutes when reconfiguring an office is just the beginning — we’ve only scratched the surface of what users can build in their spaces. Our new map models were designed to eventually support version history, multiplayer editing, interactive objects (think whiteboards or pets) and even custom objects designed by users. I’m excited to see the core team continue building out these capabilities to help our users express their creativity in the virtual world.

Special thanks to my teammates Joao Ruschel, Maxime Briand, Emily Hu, Steven Yau, David Rios and Ryan Kubik for their contributions to the virtual world and to Kumail Jaffer for reviewing my drafts.